Report on Long Valley (United States) — June 1992

Bulletin of the Global Volcanism Network, vol. 17, no. 6 (June 1992)

Managing Editor: Lindsay McClelland.

Long Valley (United States) Abrupt increase in seismicity triggered by M 7.5 earthquake hundreds of kilometers away

Please cite this report as:

Global Volcanism Program, 1992. Report on Long Valley (United States) (McClelland, L., ed.). Bulletin of the Global Volcanism Network, 17:6. Smithsonian Institution. https://doi.org/10.5479/si.GVP.BGVN199206-323822

Long Valley

United States

37.7°N, 118.87°W; summit elev. 3390 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

Southern California's largest earthquake since 1952, M 7.5 on 28 June, appeared to trigger seismicity at several volcanic centers in California. It was centered roughly 200 km E of Los Angeles. In the following, David Hill describes post-earthquake activity at Long Valley caldera, and Stephen Walter discusses the USGS's seismic network, and the changes it detected at Lassen, Shasta, Medicine Lake, and the Geysers.

In recent years, the USGS northern California seismic network has relied upon Real-Time Processors (RTPs) to detect, record, and locate earthquakes. However, a film recorder (develocorder) collects data from 18 stations in volcanic areas, primarily to detect long-period earthquakes missed by RTPs. The film recorders proved useful in counting the post-M 7.5 earthquakes, most of which were too small to trigger the RTPs.

The film record was scanned for the 24 hours after the M 7.5 earthquake, noting the average coda duration for each identified event. Some events may have been missed because of seismogram saturation by the M 7.5 earthquake. Marked increases in microseismicity were observed at Lassen Peak, Medicine Lake caldera, and the Geysers. No earthquakes were observed at Shasta, but the lack of operating stations on the volcano limited the capability to observe small events.

Film was also scanned for the 24 hours following the M 7.0 earthquake at 40.37°N, 124.32°W (near Cape Mendocino) on 25 April. Although smaller than the 28 June earthquake, its epicenter was only 20-25% as far from the volcanoes. Furthermore, both the 25 April main shock and a M 6.5 aftershock were felt at the volcanic centers, but no felt reports were received from these areas after the 28 June earthquake. Only the Geysers showed any possible triggered events after the 25 April shock. However, background seismicity at the Geysers is higher than at the other centers, and is influenced by fluid injection and withdrawal associated with intensive geothermal development.

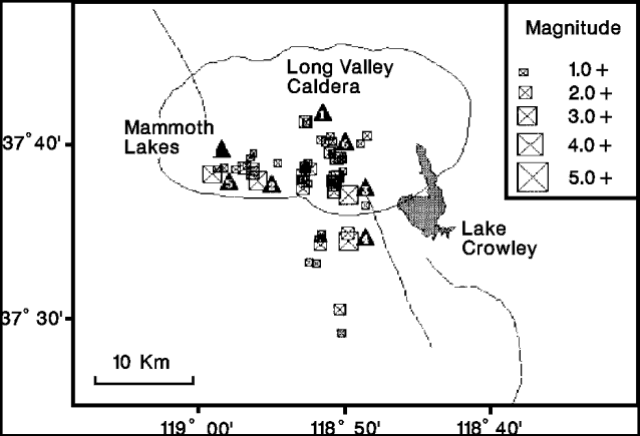

Long Valley Report. Within eight minutes of the major earthquake's origin time, seismic activity within Long Valley caldera (400 km NNW of the epicenter) increased abruptly (figure 15). Of the >260 events located by the RTP system during the next three days, three were of M 3 or greater. The first event within the caldera located by the RTP system was a M 1.4 earthquake at 1207, but develocorder film from caldera stations provides evidence of local earthquakes beginning at least a minute earlier within the strong coda waves from the M 7.5 event. The P-wave travel-time from the epicenter is just over 1 minute, and the S-wave travel-time just under two minutes, so it appears that local earthquake activity began no later than six minutes after the S-wave arrival.

Earthquake activity within Long Valley caldera had persisted, but at relatively low levels, through the first half of 1992, averaging

Geological Summary. The large 17 x 32 km Long Valley caldera east of the central Sierra Nevada Range formed as a result of the voluminous Bishop Tuff eruption about 760,000 years ago. Resurgent doming in the central part of the caldera occurred shortly afterwards, followed by rhyolitic eruptions from the caldera moat and the eruption of rhyodacite from outer ring fracture vents, ending about 50,000 years ago. During early resurgent doming the caldera was filled with a large lake that left strandlines on the caldera walls and the resurgent dome island; the lake eventually drained through the Owens River Gorge. The caldera remains thermally active, with many hot springs and fumaroles, and has had significant deformation, seismicity, and other unrest in recent years. The late-Pleistocene to Holocene Inyo Craters cut the NW topographic rim of the caldera, and along with Mammoth Mountain on the SW topographic rim, are west of the structural caldera and are chemically and tectonically distinct from the Long Valley magmatic system.

Information Contacts: D. Hill, USGS Menlo Park.