Report on Ruapehu (New Zealand) — November 2007

Bulletin of the Global Volcanism Network, vol. 32, no. 11 (November 2007)

Managing Editor: Richard Wunderman.

Ruapehu (New Zealand) Additional data on hydrothermal eruption's distribution and damage

Please cite this report as:

Global Volcanism Program, 2007. Report on Ruapehu (New Zealand) (Wunderman, R., ed.). Bulletin of the Global Volcanism Network, 32:11. Smithsonian Institution. https://doi.org/10.5479/si.GVP.BGVN200711-241100

Ruapehu

New Zealand

39.28°S, 175.57°E; summit elev. 2797 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

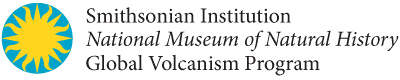

A hydrothermal explosion at Ruapehu on 25 September 2007 was previously described (BGVN 32:10), with a plume and lahars discharged from Crater Lake. Since publication, new photos and additional information was provided by Brad Scott of New Zealand's Institute of Geological & Nuclear Sciences. In addition, an article came out on the tephra dam failure and subsequent lahar (Manville and Cronin, 2007). The tephra dam broke in March 2007 (BGVN 32:10) sending a big lahar down the Whangaehu Gorge and River (figure 36).

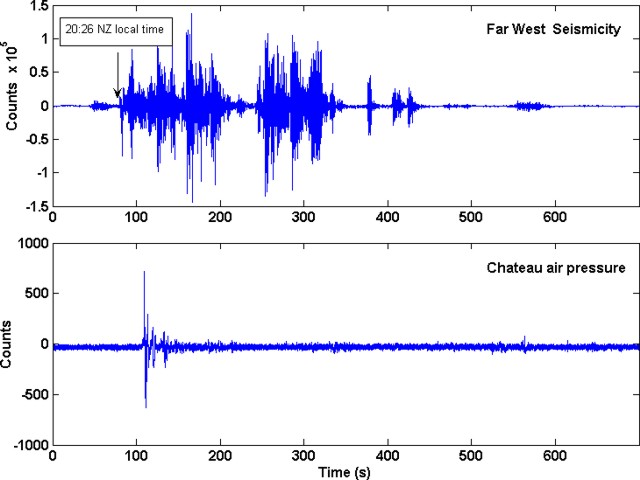

Photos of hydrothermal and lahar deposits on snow and alpine glacial ice were taken within days of the hydrothermal explosion. By 4 October, the mountain was blanketed in fresh snow, completely masking the recent deposits. Photos such as those included in this report (fresh deposits laid down on ice and snow from erupting high-altitude crater lakes) are comparatively rare.

Dome Shelter, located just N of Crater Lake, was directly in the path of the explosion. It was extensively buried by debris from the explosion and one person inside was badly injured.

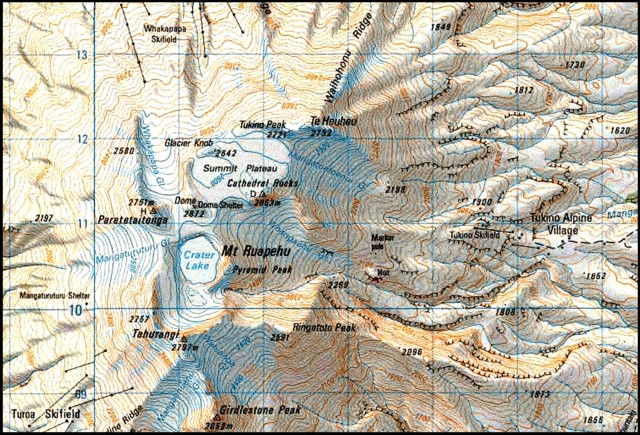

Instruments recorded seismic and air-pressure signals associated with the hydrothermal explosion (figure 37). The seismic plot shows a strong wave initially arriving at 2026 NZ local time. The velocity of sound in air is several-fold slower that the velocity of vibrations through rock (seismic waves). In addition, the sound waves were recorded at a station ~ 6 km farther away from the signal source. Consequently the sound signal's first arrival was later.

Work is still in progress to understand the complicated lahar dynamics of this event. Three main lahars descended the mountain on 25 September. Two headed roughly E (one via the outlet and associated Whangaehu Gorge, the other, larger, out over the crater walls and down a glacier). Another lahar went N (over the crater walls).

The photo of Ruapehu's summit taken from a plane, shown in figure 35 in BGVN 32:10, was a view from the NE illustrating the scene shortly after the eruption. A similar photo appears here as figure 38, although this photo was taken from the E. In both these photos, the largest (most conspicuous) lahar follows a straight path from the summit area adjacent Crater Lake. It traveled over the Whangaehu glacier.

Ejecta apparently accumulated in the N Crater basin (figure 39) before some of it flowed down the Whangaehu glacier. The latter lahar was complex, owing to eruption-blasted water followed by runoff and other possible complexities still under study. The third lahar was small and came down the Ruapehu's N side. It passed near a ski slope (figures 40 and 41).

A view of Crater Lake looking S into the crater from the Dome Shelter (figure 42) shows the strong directionality of the blast to the N (towards Dome Shelter). Numerous small blocks and bombs are visible in the foreground. Near the lake appear some lighter textured deposits on the snow (figure 42). These are rather thin (less than 0.5-1 m thick) and cross some of the darker deposits. Initial field interpretations were that these lighter deposits formed in two ways. One is the deposits mark the absorption of ejected Crater Lake water into the snow pack. The second is that they preserve the aerosol developed on the fringes of a directed blast of steam and water discharged from the Lake. Figure 43 is similar to the previous one, only viewed standing on debris farther to the E, an area where significant runoff formed a long narrow channel, which in the foreground traveled downslope towards the viewer.

Dome Shelter and news-reported injury. Dome Shelter was partly buried by typical snow accumulation, over which came the deposits from the hydrothermal eruption, some of which invaded the structure (figure 44). To summarize news stories in the New Zealand Herald and The Sydney Morning Herald, four mountaineers were camped in the Shelter during the explosion. William Pike's left leg was injured and his right leg below the knee was crushed and pinned by deposits. He was rescued and ultimately flown out by helicopter but had suffered severe hypothermia. Doctors said at one point he was very near death, with body temperature in the 25-26°C range. They managed to save him after amputating the lower portion of his right leg. The news also reported that the Shelter was designated for emergency use only (not as a camping shelter).

GNS noted that the Shelter also houses monitoring instruments, equipment less damaged than initially thought. Data from one of the two seismic systems continued to flow, although the data were rather noisy. Accordingly, GNS began relying on nearby monitoring stations.

Reference. Manville, V., and Cronin, S.J., 2007, Breakout lahar from New Zealand's Crater Lake, Earth Observing Satellite, Transactions, American Geophysical Union, v. 88, no. 43, p. 441-442.

Geological Summary. Ruapehu, one of New Zealand's most active volcanoes, is a complex stratovolcano constructed during at least four cone-building episodes dating back to about 200,000 years ago. The dominantly andesitic 110 km3 volcanic massif is elongated in a NNE-SSW direction and surrounded by another 100 km3 ring plain of volcaniclastic debris, including the NW-flank Murimoto debris-avalanche deposit. A series of subplinian eruptions took place between about 22,600 and 10,000 years ago, but pyroclastic flows have been infrequent. The broad summait area and flank contain at least six vents active during the Holocene. Frequent mild-to-moderate explosive eruptions have been recorded from the Te Wai a-Moe (Crater Lake) vent, and tephra characteristics suggest that the crater lake may have formed as recently as 3,000 years ago. Lahars resulting from phreatic eruptions at the summit crater lake are a hazard to a ski area on the upper flanks and lower river valleys.

Information Contacts: Brad Scott, Institute of Geological & Nuclear Sciences (IGNS), Private Bag 2000, Wairakei, New Zealand (URL: http://www.gns.cri.nz/); New Zealand GeoNet Project (URL: http://www.geonet.org.nz/); New Zealand Herald (URL: http://www.nzherald.co.nz/); Sydney Morning Herald (URL: http://www.smh.com.au/).