Report on Kilimanjaro (Tanzania) — April 2013

Bulletin of the Global Volcanism Network, vol. 38, no. 4 (April 2013)

Managing Editor: Richard Wunderman.

Kilimanjaro (Tanzania) 2006 rockfall takes climbers' lives; 165 my minimum age; glacial retreat; economic value

Please cite this report as:

Global Volcanism Program, 2013. Report on Kilimanjaro (Tanzania) (Wunderman, R., ed.). Bulletin of the Global Volcanism Network, 38:4. Smithsonian Institution. https://doi.org/10.5479/si.GVP.BGVN201304-222150

Kilimanjaro

Tanzania

3.07°S, 37.35°E; summit elev. 5881 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

We offer our first Bulletin report on Mount Kilimanjaro, which remains a dormant volcano. We first discuss its economic value and setting. We next mention a few of the many studies of seismically detected rockfalls at volcanoes. We next discuss a 4 January 2006 rockfall that took three climbers' lives and injured five others (Kikoti and others, 2006). An investigation looked into the accident's location and cause, improvements to the route to minimize rockfall risk, as well as further recommendations and implementation to make this approach to the summit safer. Although accidents due to rockfalls and mass wasting are common in mountainous areas, volcanoes included, this subject has not typically been a major focus of Bulletin reporting. This unusually well-documented case illustrates several approaches to mitigating similar hazards at more than just this volcano.

The next section of this report notes diminishing glacial ice on Kilimanjaro, 85% gone since 1912. The youngest age date of volcanic material on the volcano is 165,000 ± 5,000 ybp. No evidence of younger eruptions was found in studies of glacial ice on the volcano (Kimberly Casey, personal communication, June 2013).

There were several reports discussing the rockfall incident and future steps that might make the route safer. The report by Kikoti and others (2006) was issued after inspection of the Arrow Glacier area looking at various alternative routes, challenges, and recommendations and implementation.

World Heritage site and economic importance. Kilimanjaro was designated a World Heritage site in 1987. UNESCO cited Kilimanjaro as "an outstanding example of a superlative natural phenomenon" with many endangered species. Guides are required for tours and costs can range to $5,000 per person for an expedition to the summit (Py-Lieberman, 2008). Income from Kilimanjaro ecotourism is a principal source of foreign exchange for Tanzania. Income from tourism overall has grown from US $65 million in 1990 to US $725 million in 2001, and then represented roughly 10% of Tanzania's gross domestic product (World Bank/MIGA, 2002). It ranks among the world's favorite volcanoes to climb (Sigurdsson and Lopes-Gautier, 2000).

Rockfalls at volcanoes. Rockfalls represent a special kind of mass movement (mass wasting smaller than landslides) in which one or more rocks become dislodged, enters free fall, and bounces down the ground surface. The rockfalls discussed here were unusually well documented (Kikoti and others, 2006), spurring this report on a phenomena so common as to often elude mention. Rockfalls are a source of noise in seismic monitoring, sometimes masking small earthquakes at depth. Rockfall signals are often counted and reported along with various types of seismic events. Rockfall signals contribute to the average absolute amplitude of seismic signals (eg., RSAM measurements) since those measurements incorporate all the various types of seismic events, rockfall signals, and noise (Endo and Murray, 1991; Voight and others, 1998).

Rockfalls have long been thought of as a possible means of detecting larger impending mass movements and for eruption forecasting, although problems such as glaciers, seasonal melting cycles, precipitation, other noise sources, etc. complicate interpretations. Rockfalls may also be triggered by earthquakes. Regarding rockfall seismic signals at Augustine stratovolcano, DeRoin and McNutt (2012) state that "The high rate of rockfalls in 2005 constitutes a new class of precursory signal that needs to be incorporated into long-term monitoring strategies at Augustine and elsewhere." Hibert and others (2011) carried out a detailed study of rockfalls detected seismically at Piton de la Fournaise, a large shield volcano with rockfalls down steep sided caldera walls. Bulletin editors are currently unaware of past or current seismic monitoring at Kilimanjaro, short- or long-term, and if those records exist, whether rockfalls were important. The rockfall case under discussion at Kilimanjaro, release of glacial deposits down a steep slope, is very unlikely to reflect a pre-eruptive event.

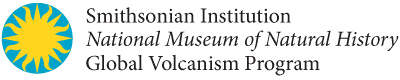

Setting and area of fatal rockfalls. Kilimanjaro sits on the East African rift, a N-trending structure spanning from Mozambique at the S to the Afar and Red Sea region at the N, a distance of 3,000-4,000 km. Kilimanjaro resides in a region where the rift has branched into Eastern and Western rift segments, with Kilimanjaro on the Eastern segment (figure 1). That branching can be seen on figure 1 traversing around Lake Victoria (Lake Nyanza).

Causes of the Accident. Extensive talus resides at the intersection between the left and right arms of the r-shaped glacier (figures 5-6). Part of this unstable talus collapsed. Kikoti and others (2006) said that the dislodged material traveled 150 m down the slope, reaching a group of people at an estimated speed of ˜40 m/sec (144 km per hour) at the point where the climbers were struck (B, figure 4).

Kikoti and others (2006) thought the talus dislodged because of (a) melting ice freeing the loose material and destabilizing it on the steep slopes, and (b) strong downhill winds measured at 177 km/h. The wind speed was measured by guide George Lyimo on the morning of the accident, using a wind speed gauge wrist unit.

Lyimo survived, having left camp ˜3 hours before the accident. Based on the known conditions at the summit, the climbers would only have had on the order of 5 seconds to escape the avalanche. Besides the strong winds, the climbers also confronted snowfall and poor visibility.

Kikoti and others (2008) examined a conspicuous cavity where the recent fallen rocks were believed to have been dislodged. They estimated that 39 tons of rocks dislodged from the cavity.

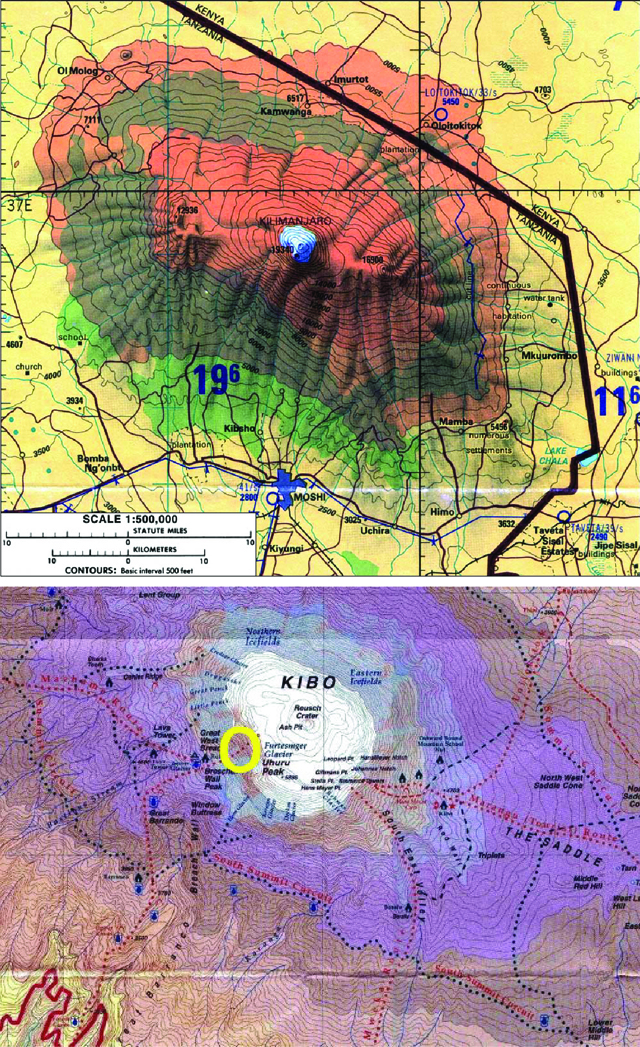

Current Status of Route. The old route (figure 3) was judged unsafe due to concern over two risk zones (A and B, figure 7). Zone A hosts residual glacial deposit at the intersection of the right and left arms of the r-shaped glacier resulting in exposure to rockfall from above. Zone B includes the crater wall and rock tower, which could shed debris from above. Above this area, the remainder of the route is judged to be subject to no specific identifiable imminent threats.

Recommendations and implementation. Kikoti and others (2006) made principal recommendations, some of which follow. As partly seen on figure 7 (yellow dotted line), the proposed new route traverses the rock feature known as the 'Stone Train' largely avoiding indicated hazardous zones. The route would proceed to a handrail up the left hand edge of the Stone Train to join the rock spur adjoining the base of the crater wall at ˜5,400 m.

Many of these recommendations were adopted and a October 2008 posting on the Mt. Kilimanjaro Travel Guide (Baxter, 2008) discussed implementation, obligations of tour operators, climbers, guides and the Park to make the route safer. These ranged from immediate steps such as asking all climbing parties to depart Arrow Glacier camp no later than 5 a.m. to mid-term steps such as the issuance by tour companies of radio handsets for guides to communicate with Kilimanjaro National Park Authority (KINAPA) rescue teams. As a result, the Park was directed to take immediate steps such as erecting signboards warning visitors of rockfall dangers and put in place a rockfall protocol and ensure that all their rescue staffs are trained on how to effectively use it.

Baxter (2008) recommended investigations by further specialists (seismologists, glaciologists, geologists, meteorologists, etc.) to assess the long term future risks associated with climate change and Kilimanjaro's altering geology and glaciology. A safety patrol team was also tasked with visiting the mountain monthly or bi-monthly to survey and identify possible future risk areas in the light of the rapidly changing situation on Kilimanjaro.

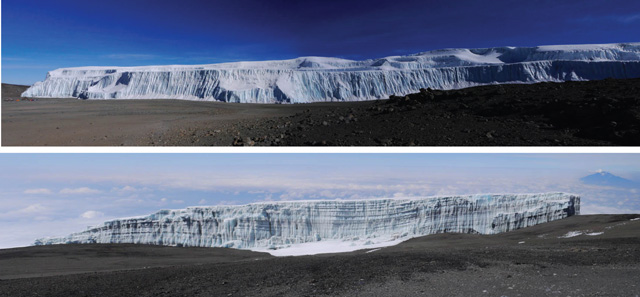

Receding glaciers. Cullen and others (2013) discuss the time series of glacial retreat at Kilimanjaro during 1912 to 2011. They concluded that 85 per cent of the glacier had disappeared. Figures 8 and 9 contain satellite imagery and land-based photos presented on a NASA Earth Observatory article (Allen and others, 2012) that describes the state of summit glaciers at Kilimanjaro on 26 October 2012. Melting ice and subsequent melt-water runoff reduce confining pressure on the magmatic system. There is evidence that such reduced pressure or loading might promote the onset of volcanism (e.g., Bay and others, 2004; Pagli and Sigmundsson, 2008; Sigvaldason and others, 1992).

According to Allen and others (2012), during a 2012 expedition, scientists found that the northern ice field, which had been developing since the 1970s then had a hole wide enough to ride a bicycle through. They also were able to walk on land directly through the rift (labeled on figure 8, right).

Cullen and others (2013) said that despite Mount Kilimanjaro's location in the tropics, the dry and cold air at the top of the mountain has sustained large quantities of ice for more than 10,000 years. At points, ice has completely surrounded the crater. Studies of ice core samples show that Kilimanjaro's ice has persisted through multiple warm spells, droughts, and periods of abrupt climate change.

Fumarolic activity occurs on the volcano, particularly in Kibu crater. Tour operator Eddie Frank (Tusker Trail) has agreed to keep a log of observed changes of color and smell at fumaroles.

Age dates of eruptive products. Nonnotte and others (2008) discussed the youngest K-Ar age date for Kilimanjaro. Samples associated with the latest parasitic phase (05KI41B and 03TZ42B) yield ages of 165 ± 5 ka and 195 ± 5 ka, respectively. "The last volcanicity, around 200-150 ka, is marked by the formation of the present summit crater in Kibo and the development of linear parasitic volcanic belts, constituted by numerous Strombolian-type isolated cones on the NW and SE slopes of Kilimanjaro. These belts are likely to occur above deep-seated fractures that have guided the magma ascent, and the changes in their directions with time might be related to the rotation of recent local stress field," Nonnotte and others wrote (2008).

References: Allen, J, Simmon, R, Voiland, A., and Casey, K, 2012, Kilimanjaro's Shrinking Ice Fields, NASA Earth Observatory-Image of the day (URL: http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/) Posted 8 November 2012; Accesssed 14 June 2013.

Baxter, P., 2008, TANAPA Western Breach Protocol—Tanzania National Parks, Obligations and Actions Regarding the Re-opening of Western Breach Route (Arrow Glacier), Mt. Kilimanjaro Travel Guide [posted 21 October 2008] (URL: http://www.mtkilimanjarologue.com/tanapa-western-breach-protocol).

Bay, RC, Bramall, N, and P Buford Price, 2004, Bipolar correlation of volcanism with millennial climate change, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004 April 27; 101(17): 6341-6345. Published online 2004 April 19. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400323101 PMCID: PMC404046

Cullen, N. J., Sirguey, P., Mölg, T. Kaser, G. Winkler, M. and Fitzsimons, S. J. , 2013.A century of ice retreat on Kilimanjaro: the mapping reloaded, The Cryosphere Discuss., 6, 4233-4265, doi:10.5194/tcd-6-4233-2012, 2012.

DeRoin N. and S.R. McNutt, 2012, Rockfalls at Augustine Volcano, Alaska: The Influence of Eruption Precursors and Seasonal Factors on Occurrence Patterns 1997-2009. J . Volcanol. Geotherm. Res., v. 211-212, p. 61-75

Endo, E.T. and Murray, T., 1991, Real-time seismic amplitude measurement (RSAM): a volcano monitoring and prediction tool. Bulletin of Volcanology 53.7 (1991): 533-545.

Hibert, C., A. Mangeney, G. Grandjean, and N. M. Shapiro, 2011, Slope instabilities in Dolomieu crater, Réunion Island: From seismic signals to rockfall characteristics, J. Geophys. Res., 116, F04032, doi:10.1029/2011JF002038

Kikoti, I., Nchereri, J.P., Mlay, A., Lyimo, G., Msemo, E., and Rees-Evans, J., 2006, Kilimanjaro Safety Patrol Reconnaissance Expedition, 25th-27th January 2006, An investigation to determine the cause of the Western Breach accident of 4th January 2006 and to offer recommendations for the way forward for this route [Report completed June 2006 and posted online at (URL: http://www.yumpu.com/en/document/view/7812851/western-breach-investigation-digital-copy)

Nonnotte, P, Guilloub, H, Le Guillou, B, Benoit, M, Cotten, J, Scaillet, S, 2008, Jour. of Volc. and Geoth. Res., Volume 173, Issues 1-2, 1 June 2008, pp. 99-112

Pagli, C., and Sigmundsson, F. (2008). Will present day glacier retreat increase volcanic activity? Stress induced by recent glacier retreat and its effect on magmatism at the Vatnajökull ice cap, Iceland. Geophysical Research Letters, 35(9), L09304.

Py-Lieberman, B, 2008, Life lists, Hiking Mount Kilimanjaro, A trek up the world's tallest freestanding mountain takes you through five different ecosystems and offers a stunning 19,340-foot view, Smithsonian magazine, January 2008 [online version, URL: http://www.smithsonianmag.com/specialsections/lifelists/lifelist-kilimanjaro.html]

Sigurdsson S., and Lopes-Gautier, R. 2000, Volcanoes and Tourism; Encyclopedia of Volcanoes, Academic Press, pp. 1283-1299.

Sigvaldason, G.E., Annertz, K., and Nilsson, M., 1992, Effect of glacier loading/deloading on volcanism: postglacial volcanic production rate of the Dyngjufjöll area, central Iceland. Bulletin of Volcanology 54, no. 5 (1992): 385-392.

UNESCO, date uncertain, Kilimanjaro National Park, UNESCO (URL:whc.unesco.org/en/list/403)

Geological Summary. Massive Kilimanjaro consists of three overlapping edifices along a NW-SE trend, mostly constructed during the Pleistocene, with an ice-capped summit that reaches 5,200 m above the surrounding plains. Kibo is the central stratovolcano, which has a broad elongated profile and a 2 x 3 km summit caldera. Activity at the older Shira cone, which forms the broad WNW shoulder of the complex, began during the Pliocene. The extensively dissected Pleistocene Mawenzi forms a prominent, sharp-topped peak on the ESE flank, dominated by a densely packed radial dike swarm. More than 250 cones occupy a rift zone to the NW and SE. Fumarolic activity is present within a group of nested summit craters. Widespread statements that the "most recent activity was about 200 years ago," sometimes referencing the central "ash pit" formation, are of unknown origin with no supporting evidence in geological or anthropological literature. Nonnotte et al. (2008) K-Ar dated caldera-rim group lavas in the 170-274 ka range, and placed the most recent volcanism (formation of both the present summit crater, Inner Crater group lavas, and flank cones) around 150-200 ka. Martin-Jones et al. (2020) attributed two mafic tephra deposits in Lake Chala to Kilimanjaro that were dated to about 248 and 134 ka.

Information Contacts: Eddie Frank, Tusker Trail, 924 Incline Way Suite H Incline Village, Nevada 89451-9423 USA (URL: http://www.Tusker.com); and Kimberly Casey, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Cryospheric Sciences Lab, Code 615, Greenbelt, MD 20771 USA (URL: http://neptune.gsfc.nasa.gov/csb/personnel/?kcasey).