Report on Pacaya (Guatemala) — August 2019

Bulletin of the Global Volcanism Network, vol. 44, no. 8 (August 2019)

Managing Editor: Edward Venzke.

Edited by Janine B. Krippner.

Pacaya (Guatemala) Lava flows and Strombolian explosions continued during February-July 2019

Please cite this report as:

Global Volcanism Program, 2019. Report on Pacaya (Guatemala) (Krippner, J.B., and Venzke, E., eds.). Bulletin of the Global Volcanism Network, 44:8. Smithsonian Institution. https://doi.org/10.5479/si.GVP.BGVN201908-342110

Pacaya

Guatemala

14.382°N, 90.601°W; summit elev. 2569 m

All times are local (unless otherwise noted)

Pacaya is one of the most active volcanoes in Guatemala, with activity largely consisting of frequent lava flows and Strombolian activity at the Mackenney crater. This report summarizes continued activity during February through July 2019 based on reports by Guatemala's Instituto Nacional de Sismologia, Vulcanologia, Meteorologia e Hydrologia (INSIVUMEH) and Sistema de la Coordinadora Nacional para la Reducción de Desastres (CONRED), visiting scientists, and satellite data.

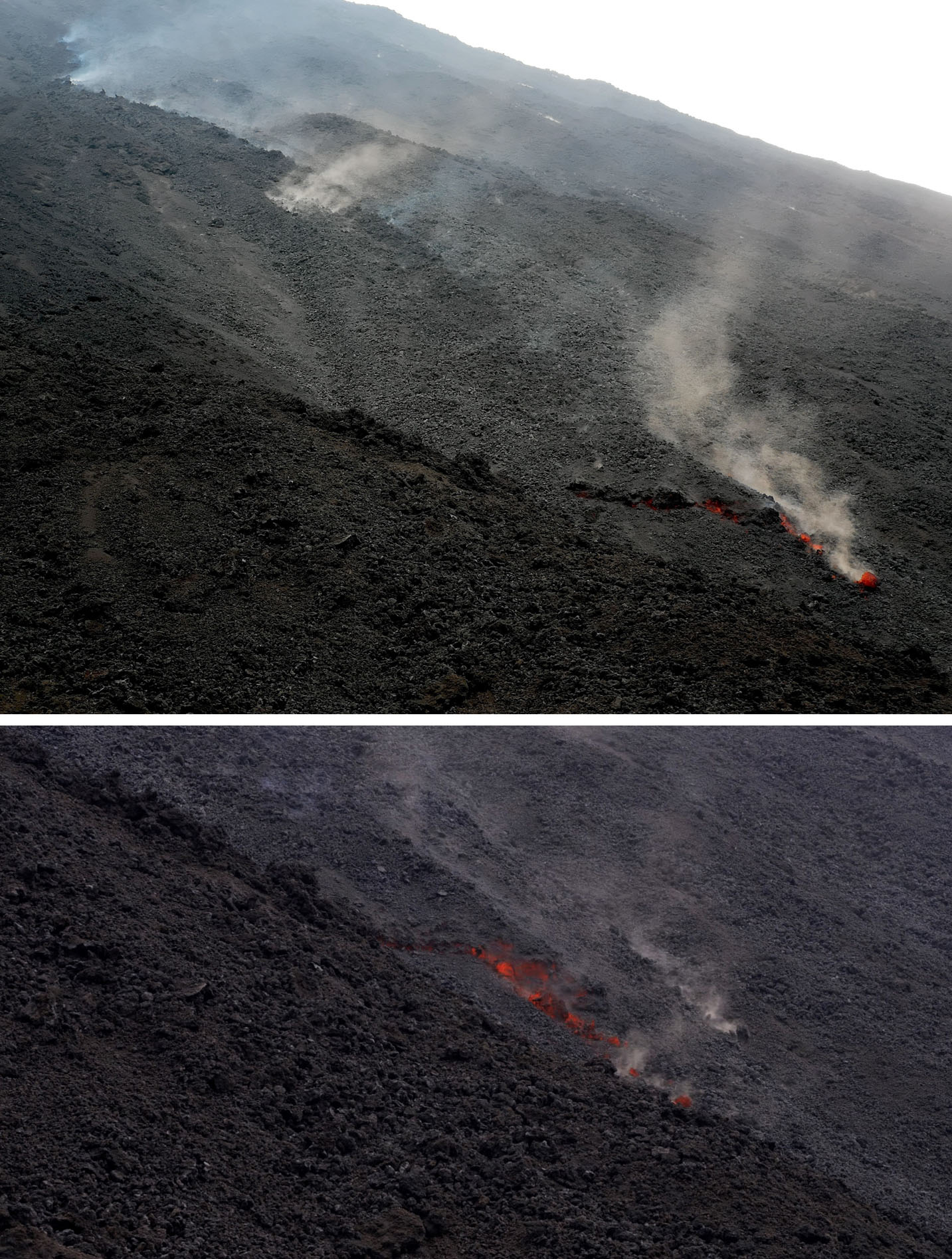

At the beginning of February activity included Strombolian explosions ejecting material up to 5 to 30 m above the Mackenney crater and a degassing plume up to 300 m. Multiple lava flows were observed throughout the month on the N, NW, and W flanks, reaching 350 m from the crater and resulting in avalanches from the flow fronts. Strombolian activity continued with sporadic to continuous explosions ejecting material 5-75 m above the Mackenney crater. Degassing produced plumes up to 300 m above the crater, and incandescence from the crater and lava flows were seen at night. Daniel Sturgess of Bristol University observed activity on the 24th, noting a 70-m-long lava flow with individual blocks from the front of the flow rolling down the flanks (figure 108). He reported that mild Strombolian explosions occurred every 10-20 minutes and ejected blocks, up to approximately 4 m in diameter, as high as 5-30 m above the crater and towards the northern flank.

|

Figure 108. An active lava flow on the NW flank of Pacaya on 24 February 2019 with incandescence visible in lower light conditions. Courtesy of Daniel Sturgess, University of Bristol. |

Similar activity continued through March with multiple lava flows reaching a maximum of 200 m N and NW, and avalanches descending from the flow fronts. Ongoing Strombolian explosions expelled material up to 75 m above the Mackenney crater. Degassing produced a white-blue plume to a maximum of 900 m above the crater (figure 109) and incandescence was noted some nights.

|

Figure 109. A degassing plume at Pacaya reaching 350 m above the crater and dispersing to the S on 19 March 2019. Courtesy of CONRED. |

During April lava flows continued on the N and NW flanks, reaching a maximum length of 300 m, with avalanches forming from the flow fronts. Degassing formed plumes up to 600 m above the crater that dispersed with various wind directions. Strombolian activity continued with explosions ejecting material up to 40 m above the crater. On the 2nd and 3rd weak rumbles were heard at distances of 4-5 km. Similar activity continued through May with lava flows reaching 300 m to the N, degassing producing plumes up to 600 m above the crater, and Strombolian explosions ejecting material up to 15 m above the crater.

Lava flows continued out to 300 m in length to the N and NW during June (figures 110 and 111). Strombolian activity ejected material up to 30 m above the crater and degassing resulted in plumes that reached 300 m. During July there were multiple active lava flows that reached a maximum of 300 m in length on the N and NW flanks (figure 112). Avalanches generated by the collapse of material at the front of the lava flows were accompanied by explosions ejecting material up to 30 m above the crater.

|

Figure 110. An active lava flow on Pacaya on 9 June 2019 with incandescent blocks rolling down the flank from the flow front. Courtesy of Paul Wallace, University of Liverpool. |

|

Figure 111. Activity at Pacaya on 22 June 2019 with a degassing plume dispersed to the W and a 300-m-long lava flow. Photos by Miguel Morales, courtesy of CONRED. |

|

Figure 112. Two lava flows were active to the N and NW at Pacaya on 20 July 2019. Photos courtesy of CONRED. |

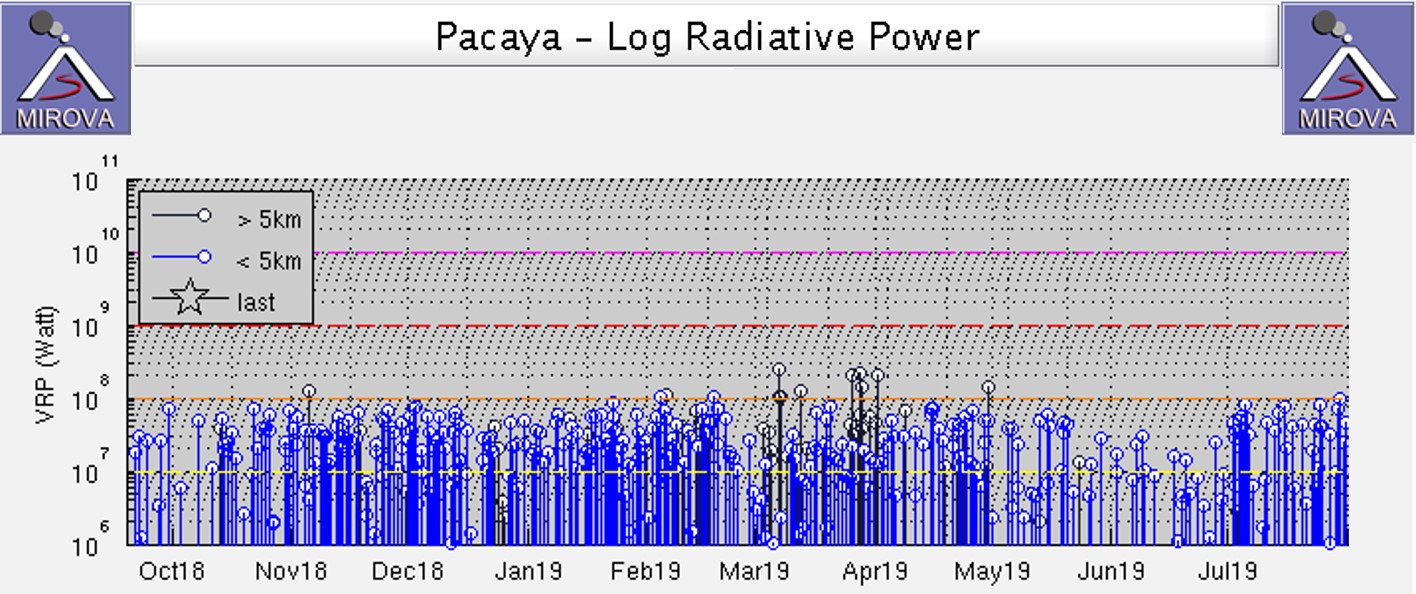

During February through July multiple lava flows and crater activity were detected in Sentinel-2 satellite thermal images (figures 113 and 114) and relatively constant thermal energy was detected by the MIROVA system with a slight decrease in the energy and frequency of anomalies during June (figure 115). The thermal anomalies detected by the MODVOLC system for each month from February through July spanned 6-30, with six during June and 30 during April.

Geological Summary. Eruptions from Pacaya are frequently visible from Guatemala City, the nation's capital. This complex basaltic volcano was constructed just outside the southern topographic rim of the 14 x 16 km Pleistocene Amatitlán caldera. A cluster of dacitic lava domes occupies the southern caldera floor. The post-caldera Pacaya massif includes the older Pacaya Viejo and Cerro Grande stratovolcanoes and the currently active Mackenney stratovolcano. Collapse of Pacaya Viejo between 600 and 1,500 years ago produced a debris-avalanche deposit that extends 25 km onto the Pacific coastal plain and left an arcuate scarp inside which the modern Pacaya volcano (Mackenney cone) grew. The NW-flank Cerro Chino crater was last active in the 19th century. During the past several decades, activity has consisted of frequent Strombolian eruptions with intermittent lava flow extrusion that has partially filled in the caldera moat and covered the flanks of Mackenney cone, punctuated by occasional larger explosive eruptions that partially destroy the summit.

Information Contacts: Instituto Nacional de Sismologia, Vulcanologia, Meteorologia e Hydrologia (INSIVUMEH), Unit of Volcanology, Geologic Department of Investigation and Services, 7a Av. 14-57, Zona 13, Guatemala City, Guatemala (URL: http://www.insivumeh.gob.gt/); Coordinadora Nacional para la Reducción de Desastres (CONRED), Av. Hincapié 21-72, Zona 13, Guatemala City, Guatemala (URL: http://conred.gob.gt/www/index.php); MIROVA (Middle InfraRed Observation of Volcanic Activity), a collaborative project between the Universities of Turin and Florence (Italy) supported by the Centre for Volcanic Risk of the Italian Civil Protection Department (URL: http://www.mirovaweb.it/); Hawai'i Institute of Geophysics and Planetology (HIGP) - MODVOLC Thermal Alerts System, School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST), Univ. of Hawai'i, 2525 Correa Road, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA (URL: http://modis.higp.hawaii.edu/); Daniel Sturgess, School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Wills Memorial Building, Queens Road, Bristol BS8 1RJ, United Kingdom (URL: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/earthsciences/); Paul Wallace, Department of Earth, Ocean and Ecological Sciences, University of Liverpool, 4 Brownlow Street, Liverpool L69 3GP, United Kingdom (URL: https://www.liverpool.ac.uk/environmental-sciences/staff/paul-wallace/); Sentinel Hub Playground (URL: https://www.sentinel-hub.com/explore/sentinel-playground).